Some of the best minds in New Zealand are now turning their minds to how to accommodate several thousand homeless Cantabrians.

The first thought, of course, is to throw up temporary accommodation around Christchurch as fast as possible.

But as we know, “temporary” has a strange way of becoming permanent (such as the post-war prefabs build in South England to house the post-war homeless, some of which are still being enjoyed now as the equivalent of NZ’s beach baches), so the better minds are already realising that it is no point simply building in haste today the slums of tomorrow.

Better instead that whatever is put up swiftly today be future-proofed to be part of something better tomorrow.

Future-proofing this temporary accommodation means more than just thinking about making provision now for the new cabling and computer-driven systems that boffins will be inventing over coming decades.

It means thinking now about things like

- the durability of materials and componentry (so what is built will last);

- making these temporary units easily expandable into something greater (and building in now the capacity and flexibility to make this happen);

- how the accommodation units are laid out (layouts that support the building of communities, with space between them for units to expand);

- incentive schemes to encourage occupants of these units to eventually become owners;

- making the units as simple to build as possible (which requires quite a bit of ingenuity in design) so that almost anyone can build and expand them (the more people capable of assembling them the more labour will be available to contribute to their rapid construction);

- using as many “off-the-shelf” systems and components as possible to avoid delays in developing new prototypes;

- and about designing the units as attractively as possible so that the good folk living in them will want to buy theirs.

The more future-proofed these units can be, the more permanent these “temporary” units can be made—which means the more “capital” in the form of air conditioning and security systems and the like can be installed; and the more infrastructure around them can be built—in the full knowledge that this investment of resources won’t be wasted down the track.

Do it right, and it will be like building Levittown all over again (for which builder Bill Levitt earned that Time cover).

Do it right, and it will be like building Levittown all over again (for which builder Bill Levitt earned that Time cover).

Or better.

Or at least as ingenious.

With that in mind, here’s just a few opening thoughts on the matter.

Designing in staged improvements

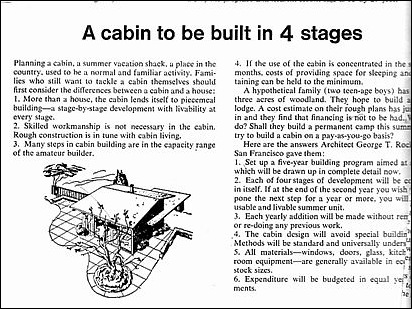

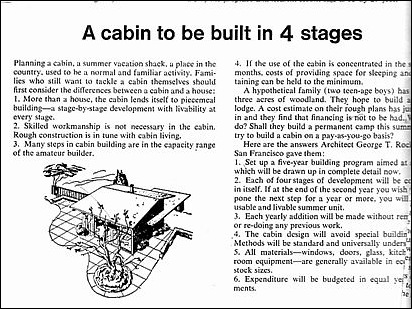

However these units are built, the more flexible their planning the better for the future. Consider as an example of the sort of flexibility these simple cabins, which have been designed so that, come the time, something much grander may be made of them. (Coincidentally, the pictures come from an old remaindered book I bought second-hand from the Canterbury Public Library some years ago.)

Now clearly I’m not suggesting just building a kitchen as the first stage of any temporary accommodation—what I’m suggesting here is a concept of how these buildings could be staged, with future modules easily added as and when needed.

Now clearly I’m not suggesting just building a kitchen as the first stage of any temporary accommodation—what I’m suggesting here is a concept of how these buildings could be staged, with future modules easily added as and when needed.

Thinking about structural systems

One of the major question to be asked about these units is “where are they going to be built.” If you want to build around fifty to one-hundred units a weeks safely and economically, you’re really talking about building in factory conditions and then trucking either panels, house sections or whole houses out to sites to assemble and place on foundations.

Some years ago I worked at a yard in Perth doing just that for a house builder called Durabilt. The houses were built in the yard on lightweight pre-stressed concrete “bridge” sections that were supremely stiff, able to support long spans, and exactly the size of a truck deck.

A simple house might consist of two, three or more of these “decks,” on which the structure was framed up using lightweight steel stud framing with all joints spot welded together—which made it both light and very, very stiff.

A two-module house could be assembled in the yard by two carpenters in around 2.5 to 3 days, with all materials being delivered to them by forklift, and all other trades programmed in. The individual truck sections were then trucked to site and set upon six large concrete rings into which the foundations were poured, and all services connected.

Hey presto, four days after the concrete deck was deposited in front of two carpenters in the yard, it was all ready to move into somewhere in the Western Australian desert. Very quick, very simple, very inexpensive, very ingenious.

Here’s a few of my old photos to give you an idea of the system:

A new one-module unit ready to go, with two new lightweight concrete “truck deck” bases in the foreground set up ready to build a two-module house.

A new one-module unit ready to go, with two new lightweight concrete “truck deck” bases in the foreground set up ready to build a two-module house.

A look under the lightweight precast pre-stressed concrete transportable deck on which the new house is built, and which becomes its floor.

A look under the lightweight precast pre-stressed concrete transportable deck on which the new house is built, and which becomes its floor.

The brown strips are tape to help release the precast concrete unit from its form.

The ribs contain the prestressed wires that give the unit its stiffness and help reduce its weight.

Already existing systems like the Firth RibRaft system could easily be adapted to make these.

Note the limited number of supports needed (just six per “deck”) which means that foundations on site can be kept to a minimum.

Lightweight steel stud framing fixed and spot-welded together on two lightweight concrete decks.

Lightweight steel stud framing fixed and spot-welded together on two lightweight concrete decks.

Cladding going up.

Cladding going up.

A house pack of prefabricated steel door frames, made up to the required sizes, delivered from the yard’s central store and ready for almost instant installation.

A house pack of prefabricated steel door frames, made up to the required sizes, delivered from the yard’s central store and ready for almost instant installation.

Door frames installed on the opening between the two modules—note the two walls, one on the perimeter of each concrete deck.

Door frames installed on the opening between the two modules—note the two walls, one on the perimeter of each concrete deck.

A single module unit packed and loaded up ready to be transported off to its new location. The common wall between the new units is tarped up, and the onsite services and fittings needed onsite are being loaded up on the “goose neck.” (Foundation rings are still to be loaded).

A single module unit packed and loaded up ready to be transported off to its new location. The common wall between the new units is tarped up, and the onsite services and fittings needed onsite are being loaded up on the “goose neck.” (Foundation rings are still to be loaded).

As you can see from these pictures, designing the simple houses around the lightweight concrete sections, using the module of a truck deck as the starting point, a very efficient construction system is possible.

Infrastructure

One issue bound to cause problems with any temporary accommodation is what to do about infrastructure, which will be the place where real “traffic jams” are almost bound to occur.

Talking about real traffic jams writer Andrew Galambos talks about them as being a collision between capitalism and socialism, where capitalism can produce cars quicker than socialism can produce roads.

A similar problem might emerge with the provision of temporary accommodation, with capitalism able to produce and erect fare more housing units than the council can provide and repair the infrastructure to which they might need to be connected (given, especially, that it seems no part of the damaged infrastructure was insured, meaning all repairs and new construction must be paid out of existing capital) .

Fortunately, solutions exist.

Stringing new electricity cables is probably the simplest job to be overcome, and could be turned into a real aesthetic bonus by offering up the design of new poles and pylons (of which literally hundreds will be covering the landscape) to design competitions. The poles and pylons themselves can help symbolise recovery.

Getting new water mains to new sites is a little more difficult, but provision for this can be made in the reconstruction of exiting roads, and on-site use of rainwater and grey water should be considered to minimise water demand.

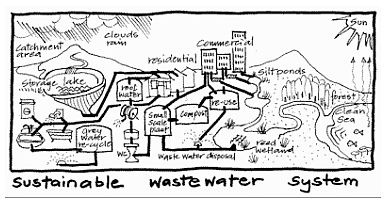

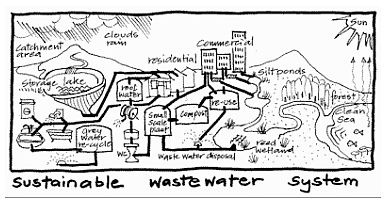

The greatest problem of infrastructure is how to get rid of waste water and storm water. Fortunately, solutions exist for this too. Instead of tapping into an already damaged centralised storm/wastewater system, with all the long delays associated with this, consideration could be given instead to onsite or decentralised disposal of waste and storm water (sometimes called “sustainable” disposal):

Doing this turns a problem into a solution.

Doing this turns a problem into a solution.

Onsite wastewater disposal systems are now legion, both for individual houses and for small “hamlets” of houses. These include sand filtration systems, evapo-transpiration systems, aerobic soakage beds, compensated dripper-line systems, wetland flow systems, and are very, very good—producing some delightful landscapes with the wastes themselves often used as compost and fertiliser.

(And their use would help encourage environmentalists who might otherwise object to these building developments to instead get in behind them, and to contribute their expertise.)

(And their use would help encourage environmentalists who might otherwise object to these building developments to instead get in behind them, and to contribute their expertise.)

By installing evapotranspiration trenches as a means of wastewater disposal, for example, the wastewater from a house can be used to establish vegetation around a house, around a park, or across a field of edible plants like alfalfa. And evapotranspiration trenches can be integrated with water harvesting swales and basins into designs to produce interesting landcape designs in a flat landscape, and to maximise food production, shade, shelter and dust mitigation. (See here for example for their use in remote Australian communities.)

It’s true that the Christchurch geology and landscape is not ideally suited to all these systems, but the expertise exists in New Zealand to select and design systems that would---and the land exists around the fringes of Christchurch to grow the crops produced.

It’s true that the Christchurch geology and landscape is not ideally suited to all these systems, but the expertise exists in New Zealand to select and design systems that would---and the land exists around the fringes of Christchurch to grow the crops produced.

Conclusion

There’s an awful lot more to be said, and these are just a very few initial thoughts about the lines down which thinking might go in providing temporary accommodation around Christchurch. And I haven’t even begun talking yet about the actual architectural design of the units themselves.

But that’s a post for another day.